Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Google Play still has a clone problem in 2019 with no end in sight

The difference between the two is subtle, but important. A clone is an app or game that looks and acts very similarly to an existing app or game, but is not a full copy. Clash of Lords by IGG is basically Clash of Clans by Supercell, with a couple of minor tweaks to the gameplay, name, and graphical assets. These are generally legal, but annoying.

A fake app tries to clone another app in name, looks, and functionality, often also adding something like malware. Despite Google’s best efforts, both types of apps remain fairly common.

Attack of the clones

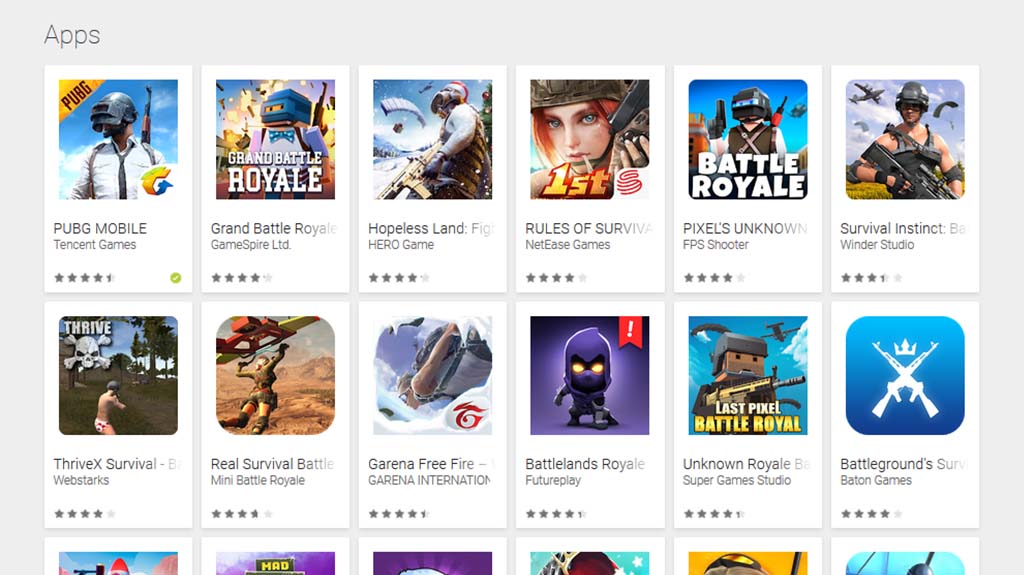

The two biggest mobile games of recent memory are Fortnite and PUBG Mobile. As you can imagine, plenty of other developers wanted in on that action. Battle royale shooters made continuous headlines, garnered millions of downloads, and took the top spots on most mobile game of the year lists. VentureBeat noted that over 100 clones made it to Google Play before either game even launched. The issue hit PUBG Mobile more than Fortnite, as Google actually took steps to prevent clones from stealing Fortnite’s action.

We’d like to say this is a new problem with a quick solution, but it’s not. Every year, a few really big apps or games are followed swiftly by a clone army invasion large enough to make even Palpatine envious. It’s a problem so old we barely even notice it anymore. Most of us simply learned how to wade through the nonsense, or we trust Google enough to put the real version as the top search result.

That didn’t change in the last year.

Fake apps and clones make everything suck more

The threat of fake apps and monotony of game clones affect consumers quite a bit. It causes trust issues and occasionally makes the Play Store confusing and irritating to use. However, if you think consumers are the only ones having problems here, consider what this can do to developers.

There’s an amusing story about how the developers of Blek (a game on iOS) received consistent emails from people complaining about advertising when Blek had no advertising. The people were playing clones and simply didn’t know it, so they complained to the actual developers of the games. Stories like that seem silly and ridiculous, but happen fairly frequently. A well placed clone can cause all kinds of havoc in the Play Store and even Apple’s App Store. In some cases, the clones end up more popular than the actual game, as was the case with the 2048 and Threes.

Fakes can cause some real problems too. In late 2017, a fake Avast app basically farmed phone numbers and five star ratings on Google Play. Google Play removed the real Magisk Manager in mid-2017, and then removed a complete malware-ridden fake in 2018. That same developer had fakes of ZArchiver, Dolphin Emulator, and KKGamer Pro. There was a fad of fake apps using Android device resources to mine cryptocurrency in 2018 as well. You can see where this is going.

Fakes and clones make everything suck and it usually causes at least some sort of damage to both developers and consumers.

Can the problem even be solved?

The problem is a little more complicated than it appears on the surface. Cloning is a problem, but in some cases it’s also legal, so Google can’t actually do anything about it. Let’s talk about the biggest problems we face with clones and fakes.

Problem One: Re-publishing is easy

The first major problem is re-publishing. A Google Play account costs a single $25 fee and an App Store developer account is $99 per year. That fee is basically pocket change to a cloner making decent money. If you ban the IP address, they can just use a VPN. If you ban the email address, they can just create another email. You can try to ban the app itself, but developers can just change a few lines of code and the package name to subvert that ban. Short of flying to the cloner’s residence and setting them on fire, there isn’t much Apple or Google can do about cloners other than just banning and removing apps when they can.

A ban or app removal is little more than a temporary annoyance to cloners and fakers.

321Mediaplyer is a clone of the popular VLC media player. That’s usually okay because VLC is open source, but 321Mediaplayer violated VLC’s licensing. It was removed in early 2018, and it went back to Google Play and accrued over 500,000 downloads before it was finally taken down. Sometimes it’s just that easy to re-publish a clone and keep it under the radar.

Problem Two: Legalese

The second major problem is the legality of it. Video game developers can copyright graphics, music, a story, character design, and a bunch of other stuff. However, they cannot currently copyright game mechanics. The reason is rather complicated, but to put it simply, a developer can’t copyright the idea of a health bar, shooting other players, or other super basic things like that. There are some exceptions, but by and large most game mechanics simply can’t be copyrighted.

Games are like paintings. You can copyright the finished work, but that's it.

Think of it like artwork. A painter can create a painting of an elephant and copyright that painting. However, that copyright doesn’t prevent other people from painting elephants. They can even use the same brush stroke technique, brand of canvas, and color palette, because you can’t copyright that stuff either. As long as it doesn’t look exactly like the original, it’s not legally considered a fake or a clone. You could end up with hundreds of similar looking elephant paintings with the same canvas, brush strokes, paint type, and colors, and that’s perfectly legal. It is very much the same with mobile apps and games.

You could just let developers copyright game mechanics, but this would destroy the game industry. After all, PUBG Mobile is a shooter, which is hardly unique. It’s not the first battle royale game, nor is it the first survival game with a last-person-standing mechanic. PUBG Mobile is a collection of ideas from other games, as are most games these days. We either let the clones live as they are or we start a horrible legal battle where the developers of Doom, Myst, and Canabalt get everybody’s money.

It's only illegal if it copies assets and code from the original game.

In the true legal sense, a clone or a fake is only truly illegal if it copies the assets and code directly from another app or game. We call them clones, but we use it as a slang term. Most game clones on Google Play are just iterations taking part in a fad. It’s a lot like why we got two volcano movies in 1997, two movies about meteors destroying Earth in 1998, or why every country music song uses electronic drum tracks now. People follow success, even if it means shamelessly riding coat tails. Unfortunately, that practice is perfectly legal.

Problem Three: Who’s job is it to fix things?

When I first started writing this article, I was going to follow the popular opinion that Google and Apple simply need to work harder to root out clones. However, Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney has a very interesting quote in this Polygon interview:

I don’t think we should fault Google or Apple for the appearance of clones. They operate stores that accept hundreds of thousands of products from the developer community, so it would be impossible to keep track of original authorship, and there’s a reasonable DMCA notice process for developers to inform them when copyright infringement does occur.

He’s right and that’s the problem. It’s not really possible or feasible for Google and Apple to judge every submission against all other submissions and existing products to see if it copies an asset or an idea. With everything we’ve talked about so far, we’d basically be asking Google and Apple to create a system that does all this:

- Sort through hundreds of thousands of submissions annually.

- Match new submissions with assets from other new submissions or existing products without false flagging legitimate use cases. This also must take into account things like licensing agreements, open source cases, and other factors that are usually external to the Play Store.

- Apply the extremely complicated laws for copyright infringement without false flagging.

- Institute a system where developers can appeal false flags that actually works.

- Operate quickly, because it’s unfair for developers to wait weeks for a submission to go live.

We still have this clone problem, even after Google removed over 700,000 apps and games from the Play Store in 2017 alone. Plus, Google doesn’t have the best history of dealing with app developers, even leaving them to deal with vague bot messages that explain nothing. Look a little further to YouTube, and creators frequently get demonetized, demoted in search rankings, and sometimes flat out banned for hidden reasons without much feedback from YouTube. Google’s AI and Search techniques are super powerful, but even they are not powerful or consistent enough to take on such a large endeavor.

Google's AI is powerful, but so far Google bots haven't done great with Google Play, Search, or YouTube.

The most logical course of action is crowdsourcing, developer intervention, and diligence. As Sweeney says, Google has a DMCA notice process for developers. There is also a flagging procedure for all of us normal people. It would take less time, effort, and money for developers and consumers to flag apps on our own rather than depending on Google (or Apple) to build, fund, and hire a whole new department to do it for us. Sometimes, the best answer is just good old fashioned hard work, communication, and paying attention.

The good news is blatant fakes are usually easy to spot, and Google is usually willing to remove them once notified. Google also does a good job of removing malware and other types of harmful or dangerous apps long before they reach our devices.

As it stands, any fully implemented system to remove illegal clones from the Play Store would actually change very little. There just isn’t much anybody can do about it unless a law changes at some point.

For now, it’s up to us and developers to root out the problems.

Heads up! We talked about this on the podcast!

Editor’s note: This post was first published in January 2019.