Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Seven years after the Nexus 7, what happened to Android tablets?

Tablets are so weird. Are they just big phones? Are they laptop replacements? Something completely different? I don’t think manufacturers even know the answer to this question.

Today marks the seven-year anniversary of the Nexus 7. This device got Google noticed in the tablet business. It helped spawn a number of devices over the next few years, like the Nexus 10, Pixel C, and Pixel Slate. Unfortunately, since then, interest in Android tablets has dropped to an all-time low. So low, in fact, Google decided to shutter its tablet division altogether, shifting employees to work on Chromebooks and other projects.

Do any of my followers use an Android tablet? Why? What’s good and what’s terrible?— David ImeI (@DurvidImel) July 8, 2019

This happened for a number of reasons, but after sourcing opinions from an enormous amount of Android tablet users, I’ve come up with a few primary factors.

Google only briefly saw tablets as a means for real productivity

In February 2011, Google released Android 3.0 Honeycomb, an OS built specifically for tablets. The update included things like resizable widgets, support for USB devices, and multiple customizable home screens — all good things for productivity! A number of tablets subsequently shipped with the goal of gaining market share over the iPad. Google quickly realized people weren’t buying iPads for productivity — they were buying them for entertainment. Bigger screens were much better for watching YouTube and reading news, and more convenient than lugging around your then-bulky laptop. If you wanted to be productive, you just used a “real computer.”

When Google released the Nexus 7 seven years ago, it focused its efforts towards just that: entertainment. Services like Google Play Movies and Google Play Books launched just a few months prior, and Google marketed the Nexus 7 as more of a souped-up e-viewer. Suddenly, users had a whole world of entertainment at their fingertips on a bigger screen. That drove a lot of initial Nexus 7 sales.

Phones got big.. and they're still getting bigger

The problem here is something Google didn’t seem to account for. As phones got a lot bigger, and processors a lot faster, the need for dedicated personal computers started to diminish. The Samsung Galaxy Note created a race for size still taking place today, and the instructions per clock (IPC) improvements in smartphone chipsets have evolved even faster than their traditional computer counterparts. Phones were getting all the attention, and tablets were deemed only a means for fun and entertainment.

Android tablets were always second-class citizens

The Nexus 7 launched with Android 4.1 Jelly Bean, an OS meant to work on both mobile phones and tablets. While it maintained some of the productivity features debuted in Honeycomb, it was clear Google was moving priority back to smartphones. Entertainment was the name of the game in mobile, and if people could view content on their phones while on the go, and shift to a bigger, more comfortable viewing experience at home, why wouldn’t they? People still had their desktops and laptops for “real work,” so productivity was left by the wayside.

Over the next few years, people’s needs rapidly shifted from “more ways to consume entertainment” to “more ways to be productive.” Games like Angry Birds were being still being downloaded, but productivity apps like Slack and Todoist took off on a global scale. People realized mobile devices could allow them to work not only in the office but also during their commute. For more basic tasks like organization, planning, and communication, smartphones worked great, but they remained less efficient for more intensive tasks like writing and video editing. People wanted more screen real-estate and a device that could keep up.

The obvious place to look for more screen is a laptop, but the world was more obsessed with portability than ever before. “Thin and light” had taken over nearly every technology segment. The logical next step was tablets.

While Android tablets were cheap and under-powered, iOS developers started looking at the iPad as a serious productivity workhorse. Developers quickly took advantage, and users were hungry to dump their laptops altogether.

Android tablet manufacturers have traditionally used low-end chips to keep costs low because, frankly, video and written content consumption is not exactly power intensive, but Apple always maintained the iPad as a flagship device. Even when its primary use case was entertainment, the iPad sported the same flagship processor as its iPhone counterpart. As the iPhone grew faster and more powerful, so too did the iPad, and developers were quick to compensate.

There was no incentive for Android app developers

Google left it to developers to optimize their apps for both phones and tablets, but Android phones were catching up with tablets in size and tablets didn’t serve any real value past content consumption. Optimizing your app for yet another device seemed useless. Letting Android naturally scale your app was the simplest option, but apps were often left with a disproportionate amount of white space and ugly interfaces.

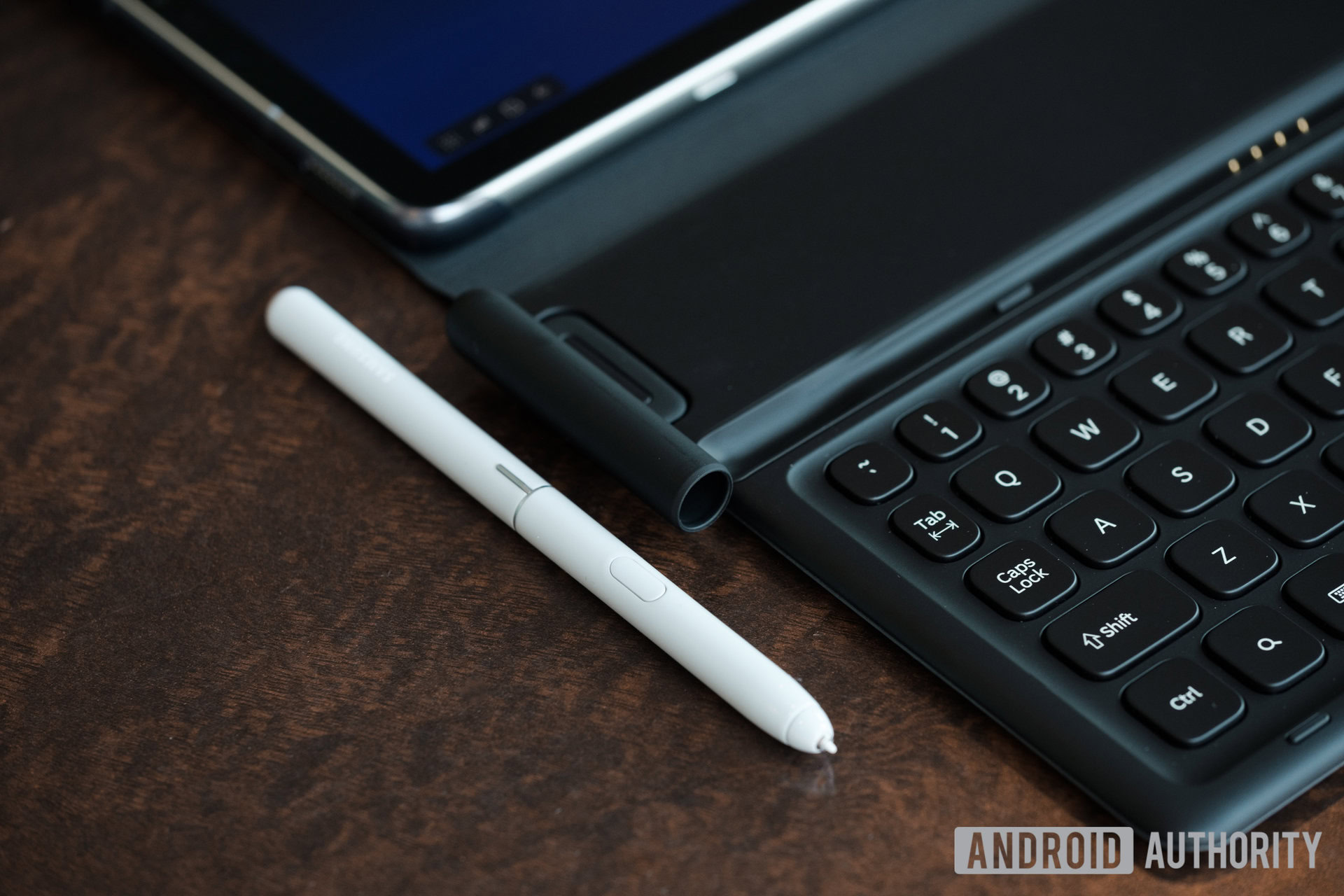

Only a few companies — notably Samsung and HUAWEI — have actually put some effort into making Android tablets become real competitors to the iPad. Samsung used flagship processors and built a pen, keyboard, and services like Dex meant to make your tablet more like a desktop. However, past Android 3.0 Honeycomb, Android was never truly optimized to support tablet interfaces. This is evident in our Samsung Galaxy Tab S4 review. While I commend Samsung’s effort in attempting to make Android a usable tablet interface, poor app optimization from developers makes just about any Android tablet a hard sell.

Google knows this, which is why it stopped developing first-party tablets with Android. The Pixel Slate runs Chrome OS, which has become the new non-mobile priority for Google. If everything is a web app and you can also run Android apps as an option, the app problem should theoretically solve itself. Unfortunately, Chrome OS was never really built for a touch interface.

The Pixel Slate seemed like a last-ditch effort for Google. After it mostly flopped, Google decided to pull out of the tablet space altogether for the time being.

What did the iPad do right?

In June, Apple unveiled iPadOS, an update geared almost exclusively towards productivity. People increasingly want to get more work done on “mobile” devices. Where phones still might not cut it due to things like a poor typing experience and a small screen, the iPad fills the void. It’s is more portable than a laptop, but more productivity-oriented than a smartphone, and Apple is leaning into that.

Honeycomb was ahead of its time.

Apple is just now adding features that debuted eight years ago in Android Honeycomb, but the world is different now. Access to external USB media, pinned desktop widgets, and split-screen functionality are all productivity features. People are happy to gobble them up in 2019. The iPad isn’t seen as a content-only device anymore — many people use them as their primary computers. Accomplished photographers Ted Forbes and Brian Matiash use their iPads every day for high-end video and photo editing, primarily due to app support from developers.

Another reason for the iPad’s success is continued support and improvement from Apple itself. Developer APIs like Metal make apps run much better on Apple hardware. Developers can quickly take advantage of that power for their productivity apps. While Google has done a great job of expanding language options, it’s hard to deny Apple’s ability to make its hardware lucrative for developers.

For consumers, a big reason to continue to buy the iPad is consistency. An iPad has always behaved like an iPad, since the very first model. If you buy one, you know what you’re getting into. The Android tablet market is at best a total crapshoot.

The Google Pixel is one of the only Google products that has had a consistent, iterative design scheme. If Google did the same with tablets, we might see some improvement that could finally convince people to switch.

What’s next?

For now, first-party Android tablets are as good as dead. Samsung and HUAWEI will keep trying to pick up the slack, but if Google isn’t invested in building software for its own hardware, it’s hard to see Android tablets leaving a meaningful impact on the broader market.

Still, I mourn for the Nexus 7. To me, that first attempt from Google felt magical, maybe because the market was still fresh and the possibilities of tablets had yet to be explored. At the end of the day, Android tablets never had a focused vision. For now, Chromebooks look to be the future for the company. We might not see any tablets from Google for a good while, but one day I hope it sees the light and makes a true iPad competitor again. The market needs it.