Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Florida court rules that police can make you surrender your phone passcode

December 15, 2016

After a man was arrested in Florida for suspected voyeurism, the Florida Court of Appeal’s Second District has ruled that the police can indeed compel him to reveal his phone passcode. Although the circumstances required for the police to demand your phone passcode are very specific, this ruling may have further legal implications in the future.

Mr. Aaron Stahl was arrested after being caught crouching down to film a woman under her skirt with his smartphone. He initially verbally consented to the police searching his iPhone 5 but later withdrew this. As we saw with the San Bernardino shooting suspect, Apple cannot and will not unlock a password or fingerprint protected iPhone for the police. This meant that Stahl was the only one with access to his phone.

Initially, a judge concluded that Stahl could not be forced into revealing his phone passcode because that would violate the US Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, which protects defendants from divulging self-incriminating evidence.

Initially, a judge concluded that Stahl could not be forced into revealing his phone passcode because that would violate the US Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, which protects defendants from divulging self-incriminating evidence. Well, that decision has been reversed by the Florida Court of Appeal’s Second District, who claims that the defendant’s passcode is not directly related to any criminal photos or videos found on his phone.

According to the ruling, under very specific circumstances, suspected criminals can be forced into divulging their passcodes:

In order for the foregone conclusion doctrine to apply, the State must show with reasonable particularity that, at the time it sought the act of production, it already knew the evidence sought existed, the evidence was in the possession of the accused, and the evidence was authentic.

The ruling is tied back to a 1988 case Doe v. United States, where the court ruled that it does not violate Doe’s constitutional rights to force him to sign a directive that would disclose his bank account records. Judge Stevens famously said, “He may in some cases be forced to surrender a key to a strongbox containing incriminating documents, but I do not believe he can be compelled to reveal the combination to his wall safe.”

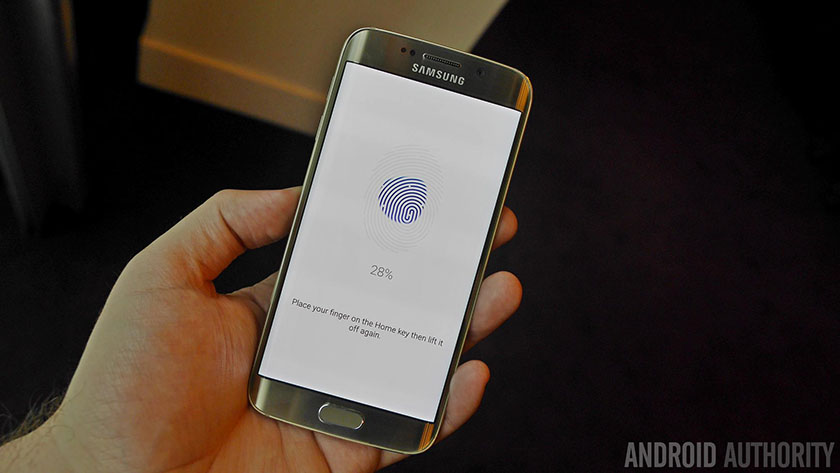

Now, the question is, as modern technology advances, what constitutes as a key to a strongbox and a combination to a wall safe? Previously passcodes were thought to be analogous to a combination to a wall safe whereas fingerprints were not. That’s why you could be forced to open your phone with your finger but not your passcode. However, the recent court decision also categorizes passcodes as a key to a strongbox, something that is not directly related to self-incrimination.

There are digital rights groups that disagree with the most recent ruling, citing that there are better ways to interpret the Fifth Amendment, but as this will potentially have far-reaching implications, the Supreme Court may eventually have to weigh in.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.